Tristan und Isolde at Deutsche Oper Berlin (2025)

Between night and light, between longing and annihilation, lies a space where love becomes both wound and salvation.

🎭 Tristan und Isolde

🎶 Richard Wagner, 1865

💭 Michael Thalheimer, 2024

🏛️ Deutsche Oper Berlin

🗓️ 09.11.2025

“VERLOSCHEN NUN DIE LETZTE LEUCHTE”

There are operas that feel intimidating before they even begin, and Tristan und Isolde is one of them. It’s Wagner’s mountain—an endless landscape of longing and dissonance, a work so total in its emotional scope that even Richard Strauss once called it “the highest fulfillment in two thousand years of theatre.” That kind of legacy doesn’t just hang over the performers; it hovers over anyone trying to stage it (or write about it).

So perhaps the smartest approach is also the simplest: Tristan und Isolde is the story of two people who love each other so deeply that the world—its rules, its structures, its daylight logic—cannot contain them. And so they turn to night, to death, to the only realm where that love might exist freely. When an unstoppable force meets an immovable object, what happens isn’t compromise, it’s combustion.

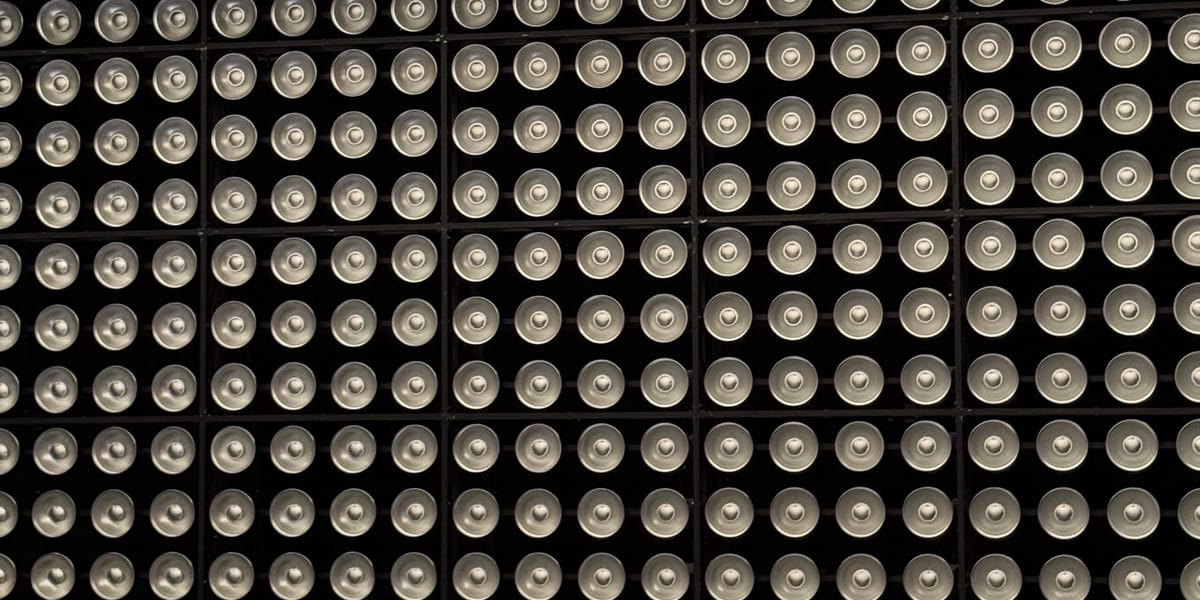

A stage reduced to heartbeat

Michael Thalheimer’s new production at Deutsche Oper understands this instinctively. It’s a staging that strips Tristan to its bare emotional core—no ships, no castles, no medieval paraphernalia. The set—walls, floor, backdrop—is black. A single movable screen of 260 lamps forms the visual heart of the piece, glowing and pulsing like a living organism. They shift in brightness, in pattern, in warmth; sometimes flickering like a heartbeat, sometimes blinding the audience in a flood of nearly unbearable light. Together with one movable block and a single rope, they are the entire vocabulary of the production. And somehow, that’s enough.

In Thalheimer’s words, this is about “concentration, reduction, simplification.” But what that minimalism does is not abstraction, it’s magnification. By clearing away all distraction, the stage becomes a void where every flicker of emotion becomes visible, every hesitation audible. The blackness works like the human psyche: a space where everything happens internally. It’s almost like Wagner’s own Inside Out—we watch these characters wander through their own emotional landscapes, each flare of the lamps like an externalized feeling.

Love burning at both ends

The lamps are more than decor; they are the drama itself. They mark day and night, passion and pain, illumination and oblivion. In moments of ecstasy, they burn so brightly you want to reach for sunglasses. In others, they pulse gently, as if breathing with the music. When Isolde first sees Tristan, the entire wall bursts into radiant light—love as explosion, love as exposure. Later, in the Act II love duet, the lights reach almost unbearable intensity. We’re literally blinded by love, and that feels deliberate. The audience is pulled into the same danger as the lovers: this light warms and consumes in equal measure, like a candle burning bright at both ends.

If light is one side of the production’s language, weight is the other. The aforementioned simple rope threads through the opera. During the Vorspiel, Isolde drags it slowly across the stage, as if pulling an invisible burden behind her. In Act III, Tristan does the same, mirroring Isolde’s struggle. Love here is both luminous and heavy, both redemption and restraint. It’s the thing that uplifts them and the thing that drowns them.

The forbidden within

Thalheimer’s Tristan isn’t a romance; it’s a study in the metaphysics of desire. The two lovers rarely touch. They reach for one another in slow motion, hands trembling, but at the last second they pull back—like magnets that repel as strongly as they attract. The one time they truly touch is in death: Isolde collapses over Tristan’s body, mirroring how his shadow earlier engulfed her on the wall.

Thus their union happens beyond life, in dissolution. In the Act II love duet, instead of physical consummation, they slit their wrists with shards from the glass that once held their love potion. It’s an image both horrifying and poetic: the same object that awakened their love now becomes the instrument of their destruction.

The program booklet draws a fascinating line between love and rebellion—a theme that feels unexpectedly current and relatable. König Marke represents society, convention, the daylight order that cannot tolerate such radical, non-conforming intimacy. But Thalheimer’s focus is psychological rather than social: the real policing happens inside. These lovers are tormented not by external punishment but by the internalized shame of wanting something that the world forbids.

The promise of catastrophe

The night becomes their refuge. As the lamps dim and the auditorium sinks into darkness, the music seems to invite introspection—that strange alertness that only comes at night, when the world is quiet enough to hear yourself think. Wagner’s “night” isn’t just the absence of light; it’s the absence of structure, a place where longing can finally be honest and vulnerable.

It’s no wonder that Lars von Trier’s Melancholia borrowed Wagner’s Vorspiel to soundtrack planetary collision. The parallel feels obvious here: like those doomed planets, Tristan and Isolde are on an inevitable crash course—love as gravity, even as catastrophe. Just as Melancholia opens with the slow-motion image of worlds colliding, announcing from the very first frame that destruction is inevitable, Tristan und Isolde carries that same fatal transparency. We hope against reason, but we already know: their love can only end in ruin. The catastrophe isn’t a twist; it’s a promise.

Even the program booklet’s astronomical imagery seems to echo that: two celestial bodies merging, annihilating each other in the process. But catastrophe in Tristan isn’t tragedy; it’s transcendence. The Liebestod, with its ethereal radiance, feels less like an ending than a supernova.

After the blinding

In those final moments, when Isolde’s voice dissolves into the orchestra, the lamps reach their brightest—the blinding climax of love and light. Then, just as suddenly, darkness. The lights go out, the music stops, and we’re left staring into the black void where it all began.

I later overheard some members of the audience murmuring, complaining, about the intense brightness, about “too much light.” But perhaps that’s the point. While the warmth of the wall of lamps is beautiful in its own way, Thalheimer’s Tristan isn’t meant to be pretty. It’s meant to overwhelm. To show that love—true, irrational, transgressive love—isn’t something we can look at directly without blinking.

And that’s what lingers after the final blackout. Not the music (though it was sublime, sung remarkably by a world-class cast), but the sensation of having looked too closely at something private, something incandescent. Anyone who has ever loved like that will recognize the impulse: to stare, to turn away, to stare again.

Maybe that’s why Tristan und Isolde still feels so alive—because it refuses to let us keep our distance. It burns, it blinds, and for a few hours, it makes us feel the dangerous, luminous, beautiful truth of what it means to want.

Cast - 09.11.2025

Conductor Sir Donald Runnicles

Director Michael Thalheimer

Assistant director Wolfgang Gruber

Stage design Henrik Ahr

Costumes Michaela Barth

Light design Stefan Bolliger

Dramaturgy Luc Joosten

Dramaturgy Jörg Königsdorf

Chorus Director Jeremy Bines

Tristan Clay Hilley

König Marke Georg Zeppenfeld

Isolde Elisabeth Teige

Kurwenal Thomas Lehman

Melot Dean Murphy

Brangäne Irene Roberts

Sheepherder Burkhard Ulrich

Seaman Kieran Carrel

Mate Paul Minhyung Roh

Chorus Chor der Deutschen Oper Berlin

Orchestra Orchester der Deutschen Oper Berlin