Tannhäuser at Deutsche Oper Berlin (2025)

A richly traditional production that opens into a sharp meditation on conformity, desire, and the cost of stepping outside of social norm.

🎭 Tannhäuser

🎶 Richard Wagner

💭 Kirsten Harms, 2008

🏛️ Deutsche Oper Berlin

🗓️ 05.04.2025

“MEIN WEG HEISST MICH NUR VORWÄRTS EILEN, RÜCKWÄRTS DARF ICH NIEMALS SEHEN.”

I wasn’t planning to write about Tannhäuser again. Having already seen this production at Deutsche Oper Berlin last year, I felt I’d said what I wanted to say. But a second encounter revealed new threads that kept tugging—some ideas familiar, others newly insistent.

At first glance, the production presents a fairly traditional image: richly medieval, grand in scale, visually rooted in romantic historicism. But beneath this surface is a more subtle—and more compelling—study of social tension and moral codes. The visual language may gesture toward conventional Wagner, but the ideas unfolding within feel anything but.

What stood out this time was how sharply the opera’s conflict maps onto a particular kind of male competitiveness. The song contest at the heart of Act II is less about love than about ideology and dominance. Tannhäuser doesn’t seem especially interested in winning; he wants to be right. His performance isn’t driven by romance but by a need to assert narrative control—Deutungshoheit—over the other men, particularly his counterpart Wolfram. Even Wolfram, whose intentions appear noble, can’t fully escape the atmosphere of performative virtue that permeates the court. This is, after all, a contest. And the stakes—honour, masculinity, purity—are unspoken but deeply felt.

Tannhäuser’s restlessness is already present in the opening scene. Bored by sensual excess in the Venusberg, he chooses to leave not out of guilt, but out of dissatisfaction. And yet, when he hears that Elisabeth awaits him, he doesn’t simply pass by. He rejoins the world he had rejected, seemingly not out of conviction but because it flatters his self-image. He wants to be wanted. He wants, in effect, to have the cake and eat it.

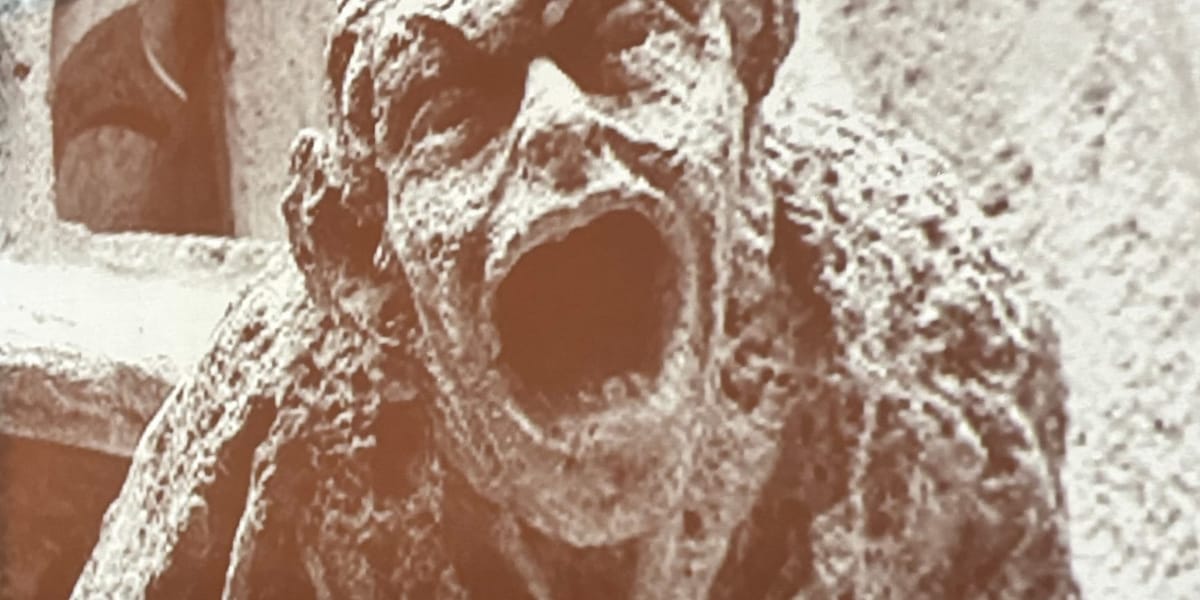

The crisis that follows—Tannhäuser’s admission of his time with Venus and the court’s explosive reaction—pushes the opera into its clearest emotional territory. It’s a moment where all pretense falls away, and the veneer of knightly civility gives way to fury and violence. In the midst of it, it’s Elisabeth who speaks with clarity, insisting on the possibility of forgiveness. But her authority rests, crucially, not on her moral reasoning, but on her purity. That she is listened to at all stems from a social contract that values her chastity more than her judgment.

In this sense, the opera’s central tension—between sacred and profane love—is embodied not in the contrast between Tannhäuser and Wolfram, but in the impossible double bind imposed on Elisabeth. Her advocacy is moving, but her options are limited. If she wishes to remain within the bounds of acceptability, she must play by the rules that bind her. Her eventual decision to send Tannhäuser to Rome and await his return doesn’t read as submission but as a painful act of agency within constraint.

The production underlines this tension with one of its most striking choices: casting the same performer as both Elisabeth and Venus. The transformation is marked not through costume but through hair—Elisabeth’s tightly wound bun giving way to Venus’ flowing, unbound style. Elisabeth literally lets down her hair to become Venus. It’s an elegant visual metaphor for the ways women are split and coded—madonna and temptress, purity and danger—despite being the same person underneath.

What emerges is not just a religious parable about sin and redemption, but a social one—about conformity, deviance, and the mechanisms through which communities police their boundaries. Tannhäuser’s transgression is framed as spiritual, but the consequences are deeply societal. The opera’s framework may be Catholic, but the logic is unmistakably civic: step outside the norm, and there is a price to pay.

Elisabeth, for all her strength and clarity, ultimately cannot change the world around her. She can only navigate it as best she can. And in the end, even as she awaits Tannhäuser’s return once more, the production leaves open the question of what, if anything, might truly change.

Cast

Conductor John Fiore

Director Kirsten Harms

Stage-design, Costume-design Bernd Damovsky

Assistance costume-design Inga Timm

Choreography Silvana Schröder

Chorus Master Jeremy Bines

Landgraf Hermann Tobias Kehrer

Tannhauser Klaus Florian Vogt

Wolfram Samuel Hasselhorn

Walther Kangyoon Shine Lee

Biterolf Michael Bachtadze

Heinrich Jörg Schörner

Reinmar Gerard Farreras

Venus, Elisabeth Elisabeth Teige

Shepherd Lilit Davtyan

Chorus Chor der Deutschen Oper Berlin

Orchestra Orchester der Deutschen Oper Berlin