Parsifal at Staatsoper Berlin

In Tcherniakov’s haunting production, a decaying ritual unfolds in a ruined chapel. A lost outsider, a cursed woman, and a broken brotherhood navigate guilt, grace, and belief in this starkly intimate post-apocalyptic vision.

🎭 Parsifal

🎶 Richard Wagner, 1882

💭 Dmitri Tcherniakov, 2015

🏛️ Staatsoper Berlin

🗓️ 15.04.2025

“DAS BÖSE BANNT, WER’S MIT GUTEM VERGILT”

Attempting to “review” Parsifal in any conventional sense feels almost absurd. Wagner’s final opus is not merely an opera—it’s a metaphysical construct, a philosophical essay in music, a sacred rite cloaked in theatrical form. To treat it like any other night at the opera would be to miss the point entirely. Parsifal is a labyrinth of sound and symbolism, a thicket of biblical allusion, medieval myth, and personal obsession. With its solemn subtitle—Bühnenweihfestspiel, or “Festival Play for the Consecration of the Stage”—Wagner envisioned this work not for casual consumption, but as the spiritual apex of his artistic vision: a replacement for the conventional religion of his time. Whether it fulfills that lofty aim is a matter of belief—but there’s no denying its singularity.

To ground ourselves, a brief summary: A naive young man named Parsifal stumbles into the realm of the Grail Knights, where King Amfortas suffers from a grievous wound—dealt by the same sacred Spear that once pierced Christ’s side—only healable by a “pure fool, enlightened by compassion.” The Spear, once in the knights’ possession, has been stolen by Klingsor, who wounded Amfortas after luring him into sin via the mysterious Kundry. Parsifal, after himself resisting Kundry’s temptations and reclaiming the Spear, returns to the Grail brotherhood in Act III to heal Amfortas, redeem Kundry, and restore the spiritual order. It’s a tale not of heroism in the traditional sense, but of awakening, empathy, and the sacred burden of understanding.

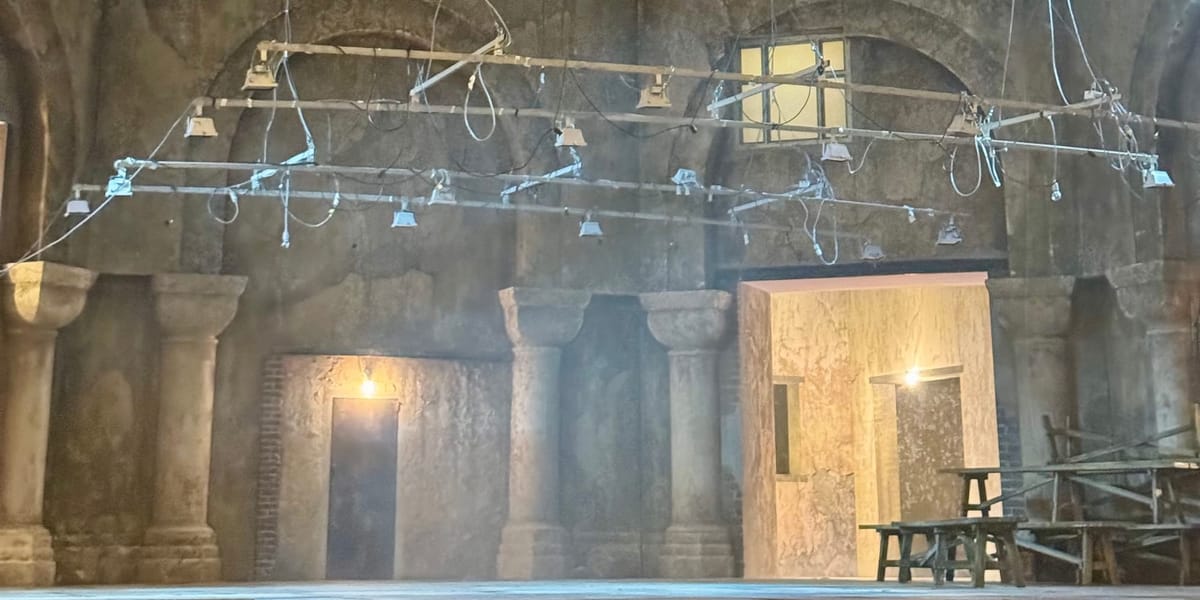

Apocalypse Now: Tcherniakov’s Cult of the Grail

Dmitri Tcherniakov’s production sets this Parsifal in a dystopian and vaguely present context, one in which the Grail community exists in a ruinous, octagonal medieval chapel—part sacred ruin, part bunker, part post-apocalyptic retreat. (Post-apocalypse seems to be a thing for Parsifal—check out the production at Staatsoper Stuttgart). The space is brilliantly realized: a lived-in shell with layers of architectural history, brickwork punctured open for large window panes; modern lighting rigs strapped onto crumbling stone. A slide show led by Gurnemanz shows us the splendor of this place in its prime, but it’s long gone. The setting evokes a world halfway between Indiana Jones and The Last of Us—a holy site that’s lost its purpose, now propped up by ritual, routine, and trauma bonding. A pre-curtain text names the knights a Männergemeinschaft—technically “brotherhood,” but here, more like a self-help cult for emotionally unavailable men in matching run-down quasi-uniforms, hiding from their pain under the veil of sacred duty.

Into this desolate enclave stumbles Parsifal, portrayed here as a confused and passive wanderer. He is clearly out of place—a dazed backpacker who stumbles into someone else’s ceremony, barely comprehending the deeply disturbing initiation ritual playing out before him. This rite, one of the production’s most haunting choices, resembles something out of a psychological horror film: the knights lying face-down en masse, Amfortas dragged forward, half-dead, forced to perform the sacraments that keep their strange community spiritually afloat. It’s terrifying in its cold, almost bureaucratic inhumanity—a sacred practice drained of meaning but kept alive through sheer inertia.

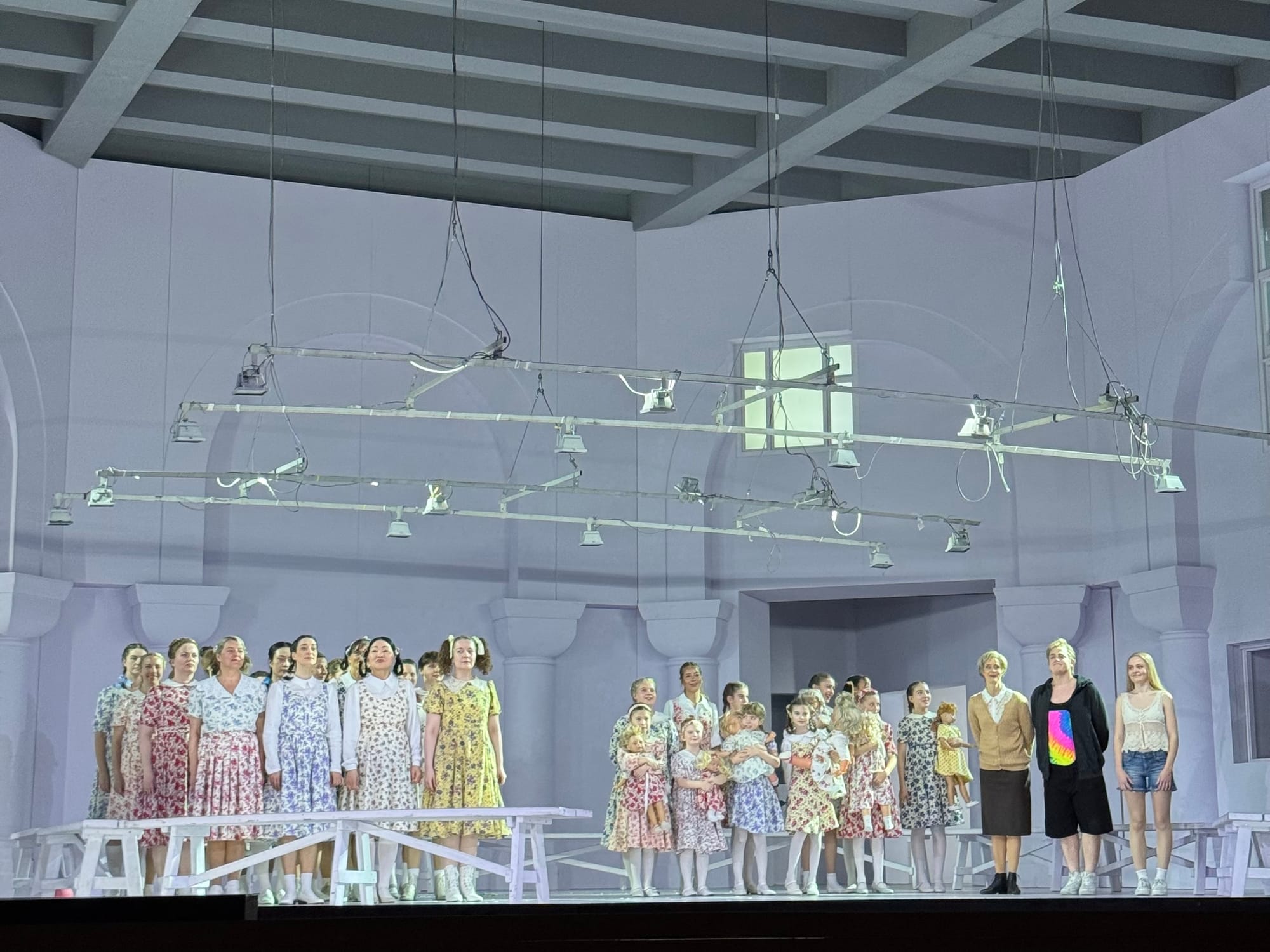

Act II offers a radical contrast. Klingsor’s realm is staged as a pastel-colored inversion of the chapel from Act I—an uncanny replica, now sanitized and decorated like a children’s playroom. Klingsor himself is a paranoid, fidgeting figure with OCD and a penchant for anxiously adjusting his greying comb-over. The flower maidens, wearing matching braids and schoolgirl dresses, transform their scene into something unsettlingly Lolita-esque. It’s difficult not to see the Knights’ susceptibility to their charms as an indictment of their own arrested development; seduced not by adult women, but by infantilized caricatures of femininity. This Act is less temptation, more fever dream—and somehow, more revealing than any sword (or Spear) fight.

A particularly striking addition is the onstage portrayal of Parsifal’s backstory during Kundry’s monologue. As she recounts his lost childhood, we witness a wordless vignette of a teenage Parsifal experiencing his first romance—only for his mother to storm in, traumatize everyone, and effectively see him self-exiled from home. The little knigh-on- horseback figurine Kundry later produces as proof of his mother’s death hits harder having seen it in that context. It’s a bold choice, and an effective one—it gives Parsifal psychological weight without reducing him to backstory.

Cursed by Compassion: Kundry and Wagner’s Theology of Suffering

In this production, Kundry remains the opera’s most compelling figure. The only female soloist, she is both scapegoat and seer, cursed and clairvoyant. According to Wagner’s invented backstory, she once laughed at Christ as he carried the cross—and for that, she is doomed to wander eternally, between names, bodies, timelines. “Never to laugh, never to weep.” Wagner’s Jesus is not the scriptural one but a mythic figure seen through a lens of medieval legend, guilt, and romantic mysticism. Kundry is not punished by theology but by narrative necessity. And yet, she is not a villain. She is the most human figure in a cast of archetypes—more complex than Klingsor, more real than Parsifal, and more tragic than Amfortas.

It’s tempting to read Parsifal through a gendered lens—and the misogyny is there. Kundry is tormented, silenced, used. Klingsor is a self-styled patriarch lording over infantilized flower maidens. The Grail knights are incapable of seeing women as anything but threats or tools. And yet, the biblical backdrop offers a strange kind of absolution. These roles feel ordained—not by any god, but by the machinery of Wagner’s inherited myths. Parsifal doesn’t escape gender essentialism; it just swallows it into its ritual structure. It is only through Parsifal’s compassion—not conquest—that Kundry finds peace (and, ultimately, also death). In that moment, at least, there is grace.

Redemption Without Dogma: Parsifal as Spiritual Reckoning

Wagner’s biblical references are unmistakable, but not canonical. The Grail and Spear aren’t drawn from scripture but from Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, and Wagner uses them not as sacred objects, but as metaphysical symbols—repositories of pain and healing. Parsifal’s journey is not a Christological imitation, but a human evolution. He becomes a redeemer not through divine mandate, but through empathy, forged in silence and sorrow. In this, Parsifal is less about salvation than about the possibility of transformation.

And what of Wagner’s Bühnenweihfestspiel? The phrase alone elevates the work beyond opera—“Festival Play for the Consecration of the Stage.” Wagner envisioned Bayreuth as a sanctuary for such a work, a space apart from commercialism where Parsifal could be staged as a sacred ritual. He refused to let it be performed anywhere else in his lifetime, and only in 1914 was it officially performed beyond Bayreuth ("illegal" performances took place as early as 1903, at the New York Met). He didn’t ask for it to be free—but he demanded it be untainted. Whether or not the Staatsoper’s €277 top ticket price fits that vision is… debatable. But there’s no question that Tcherniakov’s Parsifal delivers something close to Wagner’s ideal: an experience not just attended, but endured, contemplated, and ultimately, transformed by.

In the end, Parsifal resists easy conclusions. It is a work that asks not to be understood, but experienced—a meditation on pain, purity, and the possibility of redemption in a broken world. Tcherniakov’s staging doesn’t just present Wagner’s vision; it interrogates it, challenges it, sometimes distorts it—and in doing so, reveals its enduring, unsettling power. We are left not with answers, but with haunting images: a man forced to bless what he no longer believes in, a woman damned for a laugh, a fool who becomes wise by refusing to wound. This is not opera as entertainment. It’s opera as reckoning. And if the journey is long, bewildering, and uncomfortable—perhaps that’s the point.

Cast

Musical Director: Philippe Jordan

Director, Set Design: Dmitri Tcherniakov

Revival director: Thorsten Cölle

Assistant director: Katharina Lang

Costumes: Elena Zaytseva

Light: Gleb Filshtinsky

Amfortas: Lauri Vasar

Gurnemanz: René Pape

Parsifal: Andreas Schager

Klingsor: Tómas Tómasson

Kundry: Tanja Ariane Baumgartner

Titurel: Stefan Cerny

Knappen: Maria Kokareva, Sandra Laagus, Florian Hoffmann, Junho Hwang

Erster Gralsritter: Johan Krogius

Zweiter Gralsritter: Manuel Winckhler

Blumenmädchen: Evelin Novak, Adriane Queiroz, Sandra Laagus, Sonja Herranen, Clara Nadeshdin, Natalia Skrycka

Stimme aus der Höhe:Anna Kissjudit

Staatsopernchor, Staatskapelle Berlin

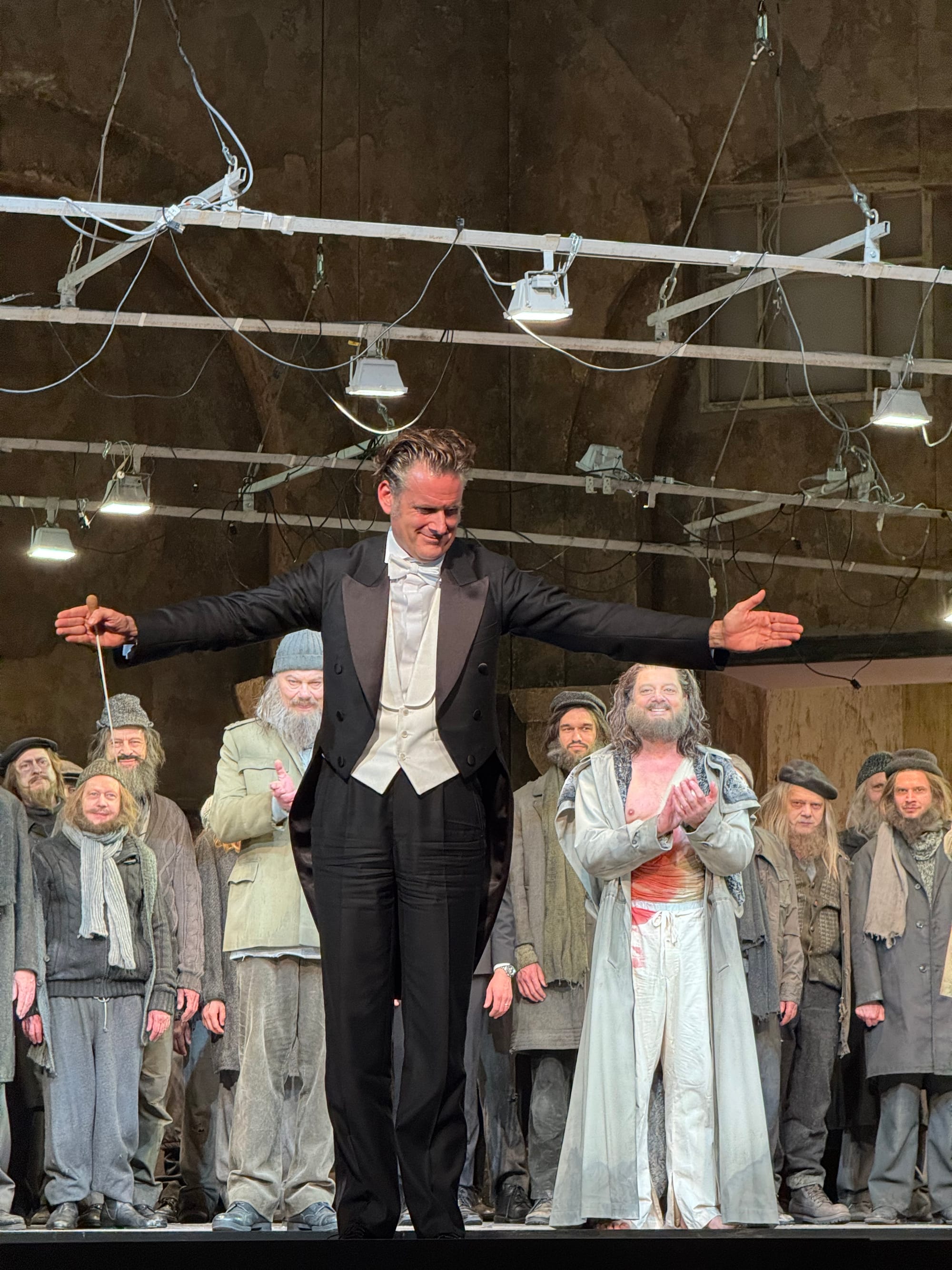

Curtain call for Parsifal at Staatsoper Berlin on April 15, 2025