Falstaff at Staatsoper Berlin

Berlin’s queer aesthetics, stripped of queerness—a glossy appropriation where underground culture becomes set dressing for straight comfort.

🎭 Falstaff

🎶 Giuseppe Verdi, 1893

💭 Mario Martone, 2018

🏛️ Staatsoper Berlin

🗓️ 20.11.2025

“THE COMMONERS MOCK ME AND ARE PROUD OF IT”

Verdi’s final opera, Falstaff, is a masterwork of comedic timing and musical sophistication—a swan song that transformed Shakespeare’s corpulent knight from The Merry Wives of Windsor into an operatic gem. This production at Staatsoper Berlin takes bold liberties with the setting, transplanting the action from Elizabethan England to 1980s (or ’90s?) Berlin, and the results are visually spectacular, musically thrilling, and—frustratingly—politically muddled.

A Berlin Fairy Tale

From the moment the curtain rises on Act I, it’s clear this production has ambitions. We open in a grungy Berlin Hinterhof, the kind of industrial courtyard space that defined the city’s alternative culture in the ’80s and ’90s. The walls are tagged with graffiti, the lighting is harsh but sparse, and the setting screams underground nightlife. Falstaff inhabits this world—a disheveled punk living next to a bar, surrounded by the detritus of Berlin’s counterculture. The bar itself? It’s called Panorama Bar, a cheeky reference to one of the world’s most iconic gay clubs.

Later, the production pivots to a sleek, modern poolside mansion—less distinctly Berlin, perhaps, but still effective as a visual contrast. The wealthy characters who scheme against Falstaff occupy this space: they’re dressed in chic, expensive clothing, lounging by the pool in a setting that reeks of privilege. The final act transforms into a rave in an abandoned industrial building, complete with fetish wear, leather harnesses, and strobing lights. Visually, this production is a feast! There’s always something to watch, some detail to catch. The staging is dynamic, the sets are gorgeous, and the aesthetic choices create a cohesive world that feels lived-in and intentional.

Comedic Excellence

What makes this production truly shine is how well it captures the comedic spirit of Verdi’s score. Falstaff is, at its heart, a farce—a story of vanity, delusion, and humiliation—and this production leans into that with gusto. The singers don’t just perform; they act. The physical comedy is spot-on, the timing is impeccable, and there are genuine laugh-out-loud moments throughout. Falstaff’s pratfalls, his indignation, his pathetic attempts at seduction—all of it lands with theatrical precision.

The music, too, is handled beautifully. Verdi’s late style is conversational, quicksilver, full of wit and sparkle, and the Staatsoper orchestra captures that effervescence. The ensemble scenes crackle with energy, and the famous fugue that closes the opera feels earned and joyful. This is an opera that can feel overly refined or stuffy in the wrong hands, but here it's kurzweilig—breezy, fun, genuinely entertaining.

The Problem: Borrowed Aesthetics, Sanitized Politics

And yet, for all its visual and musical brilliance, this production stumbles in ways that are hard to ignore. The decision to set Falstaff in 1990s Berlin and borrow so heavily from queer nightlife aesthetics feels, at best, superficial, and at worst, appropriative.

Let’s be clear: Berlin’s underground club culture in the ’90s was fundamentally queer. Panorama Bar, the fetish parties, the raves in abandoned buildings—these were spaces created by and for queer people, often in the face of police harassment, social stigma, and outright violence. To invoke this world so explicitly and then strip it of its queerness is a strange choice.

In this production, the bar is full of straight couples. The rave scene features men and women in leather and harnesses, but every interaction is heterosexual. When there is same-sex interaction—two women making suggestive poses—it’s clearly performed for male consumption. At one point, one of Falstaff’s companions makes a flirtatious advance toward him, and Falstaff recoils in visible disgust. It’s played for laughs, but the underlying message is uncomfortable: queerness as punchline, male intimacy as something grotesque.

There’s even a moment where the straight characters appear disgusted by male intimacy they witness. The police raid on the fetish party—a direct echo of the real raids that queer parties endured throughout the ’80s and ’90s—feels hollow when applied to a sanitized, straight gathering. What was transgressive about these spaces wasn't the leather or the harnesses; it was the queerness itself. To appropriate the aesthetics while erasing the people who created them feels like a betrayal of the world the production claims to inhabit.

Class and Complicity

There’s another layer to this production that complicates things further: class. The people who humiliate Falstaff are visibly wealthy. They wear expensive clothes, live in a mansion, move through the world with ease and confidence. Falstaff, by contrast, is a grungy outsider, a punk living on the margins. The humor of the opera depends on his humiliation, but in this production, that humiliation takes on a classist edge. Wealthy, powerful people are using their resources to toy with someone who has far less.

Yes, Falstaff is a flawed character—vain, lustful, misogynistic—but there’s something unsettling about watching the rich make a fool of the poor for entertainment. The production doesn't seem entirely aware of this subtext, or if it is, it doesn’t do much to interrogate it.

A Missed Opportunity

The frustrating thing is that this production was so close to being genuinely radical. It had all the pieces: the aesthetic vocabulary of Berlin counterculture, the historical context of queer resistance, the class dynamics, the punk politics. But instead of engaging with those elements meaningfully, it uses them as set dressing. The graffiti is tame, the anti-war banner feels tokenistic, and the queerness is nowhere to be found.

Opera productions matter. They shape how audiences understand stories, how they see the world. A production this high-profile, this visually ambitious, had an opportunity to frame queerness and counterculture in a positive, truthful light. Instead, it sanitized those elements for a middle-aged, heteronormative Staatsoper audience, keeping the aesthetics but discarding the politics.

The Verdict

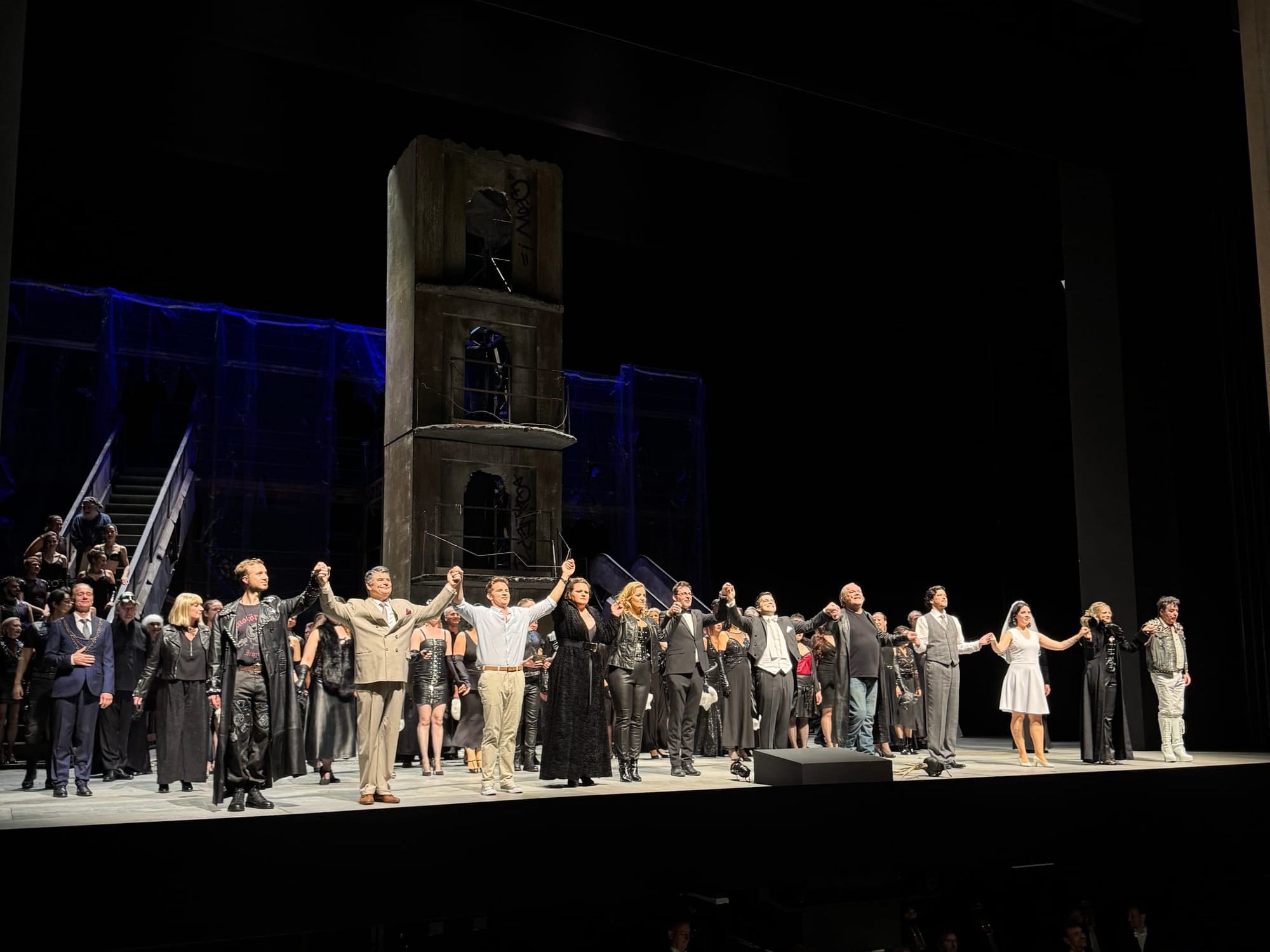

Despite my frustrations, I can’t deny that this is an impressive production. The staging is gorgeous, the performances are excellent, and the comedic energy is infectious. If you’re looking for a fun night at the opera, you’ll get it. And yet, I wish it had been braver: I wish this Falstaff had honored the world it borrowed from, rather than simply mining it for cool visuals.

Cast

Musical Director: Giuseppe Mentuccia

Director: Mario Martone

Revival director, assistant director: Marcin Łakomicki

Set Design: Margherita Palli

Costumes: Ursula Patzak

Light: Pasquale Mari

Choreography: Raffaella Giordano

Chorus Master: Gerhard Polifka

Sir John Falstaff: Michael Volle

Ford: Andrè Schuen

Fenton: Jonah Hoskins

Dr. Cajus: Jürgen Sacher

Bardolfo: Karl-Michael Ebner

Pistola: Friedrich Hamel

Mrs. Alice Ford: Gabriela Scherer

Nannetta: Rosalia Cid

Mrs. Quickly: Anna Kissjudit

Mrs. Meg Page: Rebecka Wallroth

Staatsopernchor

Staatskapelle Berlin