Elektra at Deutsche Oper Berlin

A haunting, sand-filled descent into grief, obsession, and the weight of inherited trauma—where even wealth or pearls of wisdom won’t save you from being slowly pulled under.

🎭 Elektra

🎶 Richard Strauss, 1909

💭 Kirsten Harms, 2007

🏛️ Deutsche Oper Berlin

🗓️ 01.04.2025

“LIEBE TÖTET, ABER KEINER FÄHRT DAHIN UND HAT DIE LIEBE NICHT GEKANNT!”

Richard Strauss does not ease the listener—or viewer—into Elektra. There is no overture, no measured introduction. From the instant the curtain begins to rise, we are already mid-crisis: servants rush across the stage as the opera’s iconic opening chords crash from the pit (the orchestral one—we’ll get to the stage pit in a minute), setting the tone for what is to follow. Kirsten Harms' production at Deutsche Oper Berlin embraces this momentum with a staging that is as visually austere as it is psychologically loaded. Instead of a conventional palace courtyard, we are presented with a golden-walled shaft, the top of which remains perpetually out of view. The action unfolds at the bottom, where the ground appears to be filled with sand—behaving almost like quicksand—through which all characters must trudge, sinking just slightly as they move, giving the whole piece an unsettling physical tension. It’s as if Mycenae itself is trying to consume its cursed inhabitants—one dusty, dragging step at a time.

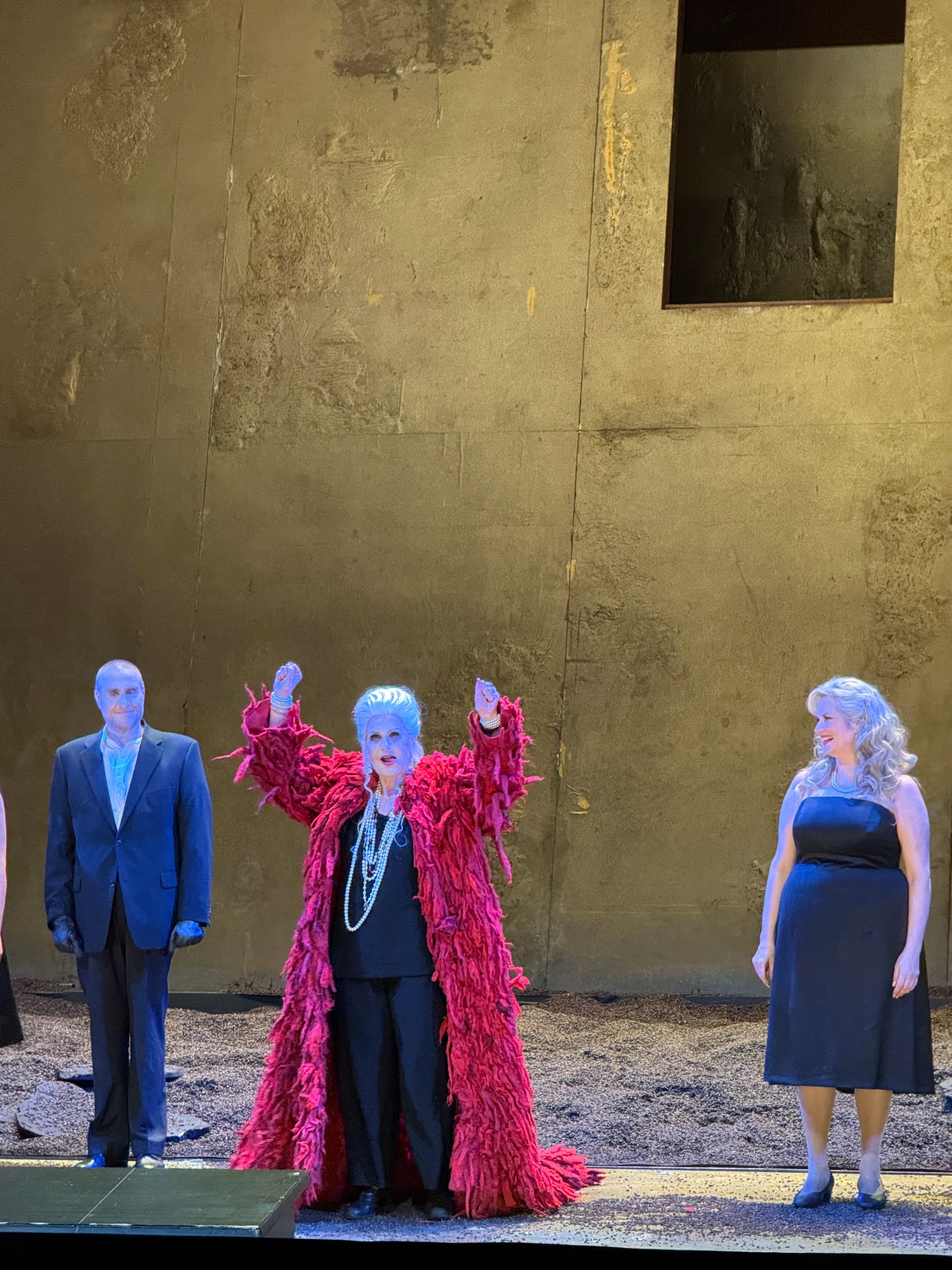

This conceit reaches a particularly powerful moment when Elektra, in one of the opera’s most infamous episodes, begins to dig. In most stagings, this gesture reads as symbolic. Here, it becomes disturbingly literal: she claws at the sand like a woman possessed, attempting to bury or exhume some unspeakable thing. And even before her entrance, the production establishes a dissonant visual palette. The servants, dressed in black cocktail dresses and pearls, evoke mid-century Americana—a kind of Jackie Kennedy-on-the-verge chic. This aesthetic dissonance is not played for irony but rather for unease: beneath the polished appearances lies a deep moral rot. When Klytämnestra arrives, she is visually aligned with her attendants, but grander and more grotesque, an entrance nothing short of imperial. Swathed in a heavy, fur-like red coat and drowning in pearls, she looks like a corrupted goddess from some alternate timeline—part Medea, part Fifth Avenue matriarch.

Lighting plays a particularly transformative role in this staging. The lighting design manipulates the golden metallic walls into appearing, at various times, as copper, silver, or burnished gold. These shifts—achieved solely through changes in hue and temperature of the lighting—give the space a chameleonic quality, reflecting the mood on stage. At times, the set suggests a burial chamber, at others, a treasure vault, or even a crucible. This mutability serves the drama well, reflecting the instability of both the house and the psyche at its center.

Klytämnestra’s costuming, too, seems to invite a reading beyond the literal. When in the original libretto she remarks “Darum bin ich so behängt mit Steinen”, it is in reference to her amulets of divine protection. In this production, the emphasis seems to shift subtly: her wealth becomes her shield; her bejeweled armor becomes more than just a fashion flex. The pearls are no longer simply charms, but emblems of the belief—well-founded or not—that wealth can insulate one from the consequences of one’s actions: the talismanic power of luxury in a world where consequences are negotiable, or at least delayable. Divine protection is out; the platinum credit card is in. In our timeline, billionaires literally flee to space to outrun accountability. In Klytämnestra’s, it’s strands of pearls and a fur coat.

Another element that reinforces this ongoing meditation on wealth and power is the horizontalization of the stage. While the majority of the action takes place in the sandy pit, the production offers glimpses into the palace proper through a high, door-like opening carved into the metallic upper wall—an aperture so far removed from the main playing area that it feels almost divine in its distance. Two additional access points, less grandiose, are located at ground level, allowing characters to enter and exit the pit. I won’t dwell too long on the Star Wars trash compactor vibes—though the slanted walls certainly encourage the association, and one half expects them to begin inching together with the score’s crescendo. Still, the architectural structuring is crucial: we first encounter Klytämnestra peering down through the high opening, observing Elektra below with a complex blend of pity, disdain, and amusement. Draped in her Saks-on-Fifth ensemble and literally above the fray, she becomes a vision of untouchable privilege—a woman who believes her elevated position absolves her of guilt, and perhaps even of gravity.

ELEKTRA von Richard Strauss, Deutsche Oper Berlin, copyright Bettina Stöß

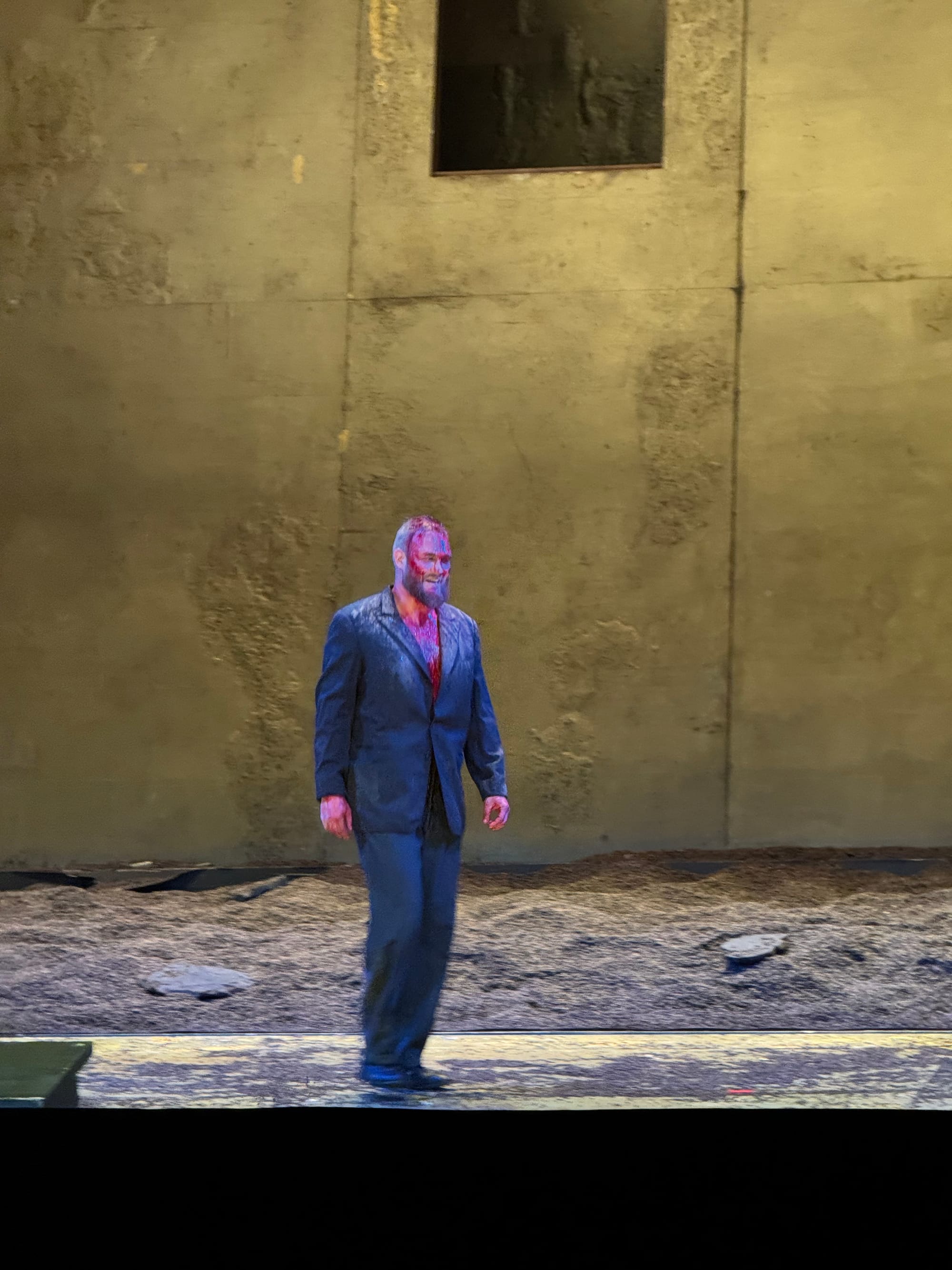

It is also, for the record, the bloodiest Elektra I have seen to date. Though Orest’s revenge still unfolds offstage—true to form, we witness the murders only through the echoing, animalistic shriek of Klytämnestra—the aftermath is impossible to miss. Orest returns, moments later, standing in the same elevated opening through which his mother once surveyed the courtyard. Now, however, it is he who dominates the vertical axis, his torso bare and covered in blood, his face equally blood-drenched and impassive. It is a startling inversion: the new heir, drenched in the evidence of matricide, positioned high above the pit like a statue of vengeance or a god of death. Whatever cleansing power this violence was meant to have, it arrives already corrupted.

While Elektra thus far hasn't become my personal favorite among Strauss’ operas (it’s Die Frau ohne Schatten, in case you’re wondering), I find myself increasingly persuaded by it with each new encounter. The work’s brevity and structural compactness intensify its impact: there is no digression, no relief. Instead, we are confronted with a single, continuous psychic wound. The score is relentless, the emotional terrain brutal, and the focus on Elektra’s emotional experience—her grief, her rage, her refusal to forget—gives the opera a stark and enduring power.

This production does not attempt to soften any of that. Rather, it heightens the claustrophobia and despair by making it physically manifest. Everyone sinks. Everyone carries weight. Elektra isn’t about resolution—it’s about obsession, trauma, and the refusal to move on. Here, she doesn’t just metaphorically wallow in her grief. She’s literally waist-deep in it. And by the time the final bloody chords hit, you’re right down there with her.

Cast

Conductor: Thomas Søndergard

Director: Kirsten Harms

Set-design, costume-design: Bernd Damovsky

Chorus Master: Jeremy Bines

Choreographer: Silvana Schröder

Klytämnestra: Doris Soffel

Elektra: Elena Pankratova

Chrysothemis: Camilla Nylund

Aegisth: Burkhard Ulrich

Orest: Tobias Kehrer

Der Pfleger des Orest: Jared Werlein

Die Vertraute: Hye-Young Moon

Die Schleppträgerin: Sua Jo

Ein junger Diener: Thomas Cilluffo

Ein alter Diener: Michael Bachtadze

Aufseherin: Maria Motolygina

1. Magd: Annika Schlicht

2. Magd: Martina Baroni

3. Magd: Arianna Manganello

4. Magd: Maria Vasilevskaya

5. Magd: Nina Solodovnikova

Chorus Chor der Deutschen Oper Berlin

Orchestra Orchester der Deutschen Oper Berlin

Dancers Opernballett der Deutschen Oper Berlin