Don Giovanni/Requiem at Komische Oper Berlin

A hallucinatory journey through guilt, lust, and liberation—set in a liminal world where spirits linger, identities blur, and music becomes a final act of grace.

🎭 Don Giovanni/Requiem

🎶 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1787

💭 Kirill Serebrennikov, 2025

🏛️ Komische Oper Berlin

🗓️ 09.05.2025

“HIER LEHREN DIE TOTEN DIE LEBENDEN!“

With Don Giovanni/Requiem, Kirill Serebrennikov concludes his Mozart–Da Ponte trilogy at the Komische Oper Berlin. What connects these three operas—beyond their shared compositional history—is a recurring narrative tension: women vs. men, rich vs. poor, life vs. death. But among these, one contrast feels inherently different. In Don Giovanni, the opposition between life and death takes center stage, giving this production a markedly different tone than Così fan tutte or Le nozze di Figaro. While it speaks the same Serebrennikovian language, Don Giovanni speaks it in a different dialect—one deeply preoccupied with the threshold between existence and absence.

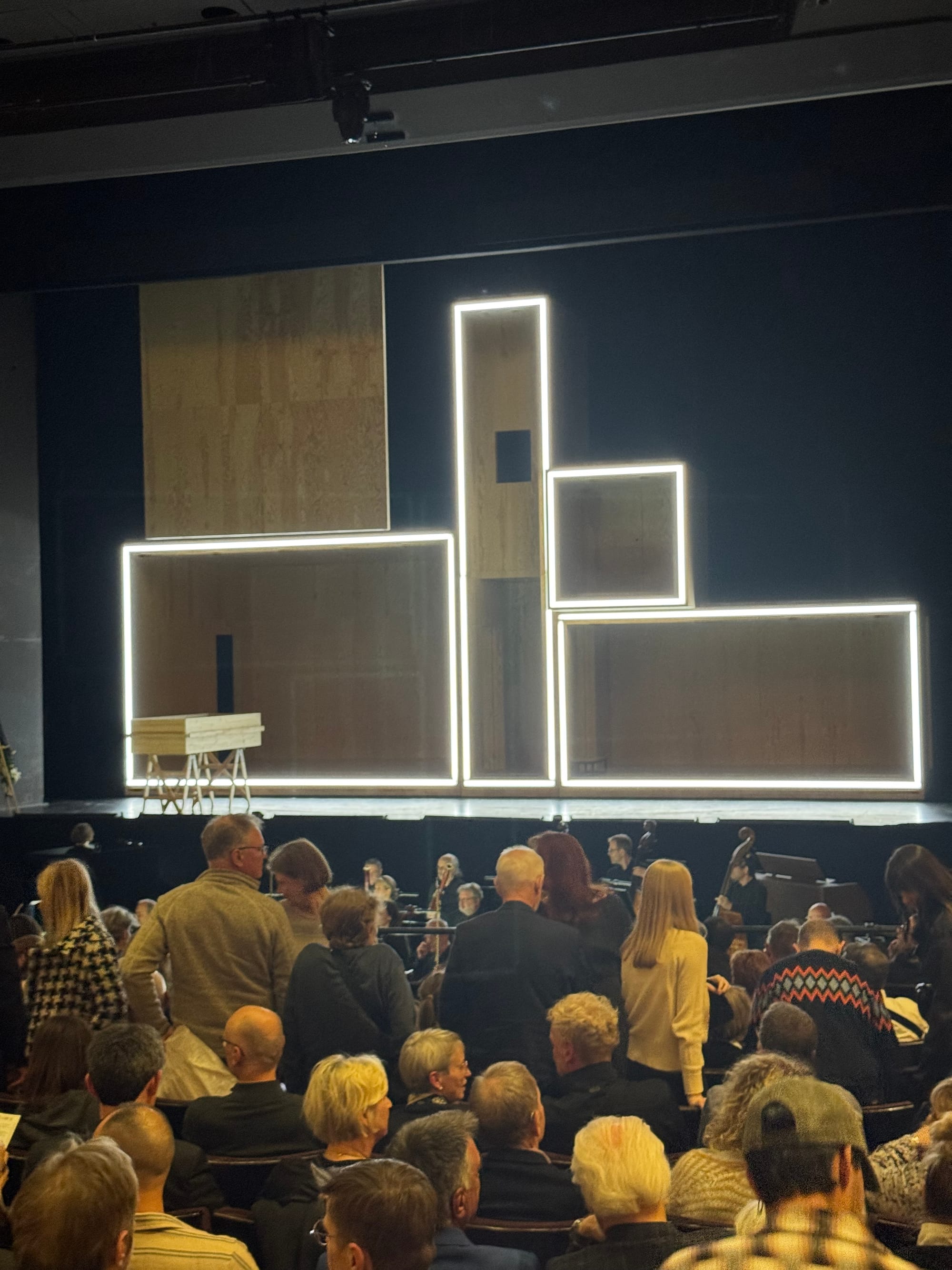

The set, built from rotating, modular boxes of raw wood, discards any ambition of realism. Unlike the previous two parts of the trilogy, this staging is neither a bedroom nor a gallery. It’s a liminal space, underscoring the in-between state that defines the entire production. We’re not watching the story of Don Giovanni unfold in real time—we’re watching it unravel in his mind, or perhaps his soul, as he journeys from life to death and back again.

Memory, Purgatory, and the Collapse of Time

This Don Giovanni is not a straightforward narrative, but a reconstruction—an Umbau, a retrospective of a life. It’s structured like a purgatory, or more precisely, like the final Bardos in the Tibetan Book of the Dead: an in-between state where one reflects, relives, and ultimately faces liberation or rebirth. The overture opens with Giovanni’s funeral. He rises from his coffin not to continue life, but to revisit it—through flashbacks, hallucinations, and fever dreams. The result is a constant sense of dislocation, where the boundaries between memory, delusion, and time itself are porous.

In this world, the narrative moves according to its own laws. The production offers no linearity and certainly no moral clarity. Instead, it invites us to observe Don Giovanni not as a sinner to be judged, but as a human—flawed, charming, violent, remorseful. The context has shifted: away from Christian notions of sin and punishment, and toward a more introspective, karmic perspective. Serebrennikov strips away the moralizing finale—the sextet of the original composition is replaced with movements from Mozart’s Requiem, reframing the ending as one of reflection rather than condemnation.

The implications are significant. Rather than casting Giovanni as the archetypal philanderer to be punished, we’re asked to see him through a more forgiving, human lens. He’s less the rapist-murderer archetype and more of a homo ludens, a pleasure-seeking, broken man moving through a grey zone of morality. We learn of his many sexual (and possibly romantic) conquests—but also of the guilt he carries, especially for the murder of the Commendatore. That act stands apart from his other misdeeds. Here, Don Giovanni is not absolved, nor condemned. He’s simply presented, with all his contradictions intact, and we, like karma, are left to decide his fate.

The parallel to the Bardo Thödol is more than thematic. Its literal translation—“liberation through hearing in the intermediate state”—gives a striking resonance to the opera’s structure. If we, the audience, are bearing witness to Giovanni’s life and death in operatic form, and to the Requiem that follows, could that act of listening itself be his redemption? Is this performance his ritual passage?

Photos: Frol Podlesnyi / Komische Oper Berlin

Queerness as Texture, Not Theme

In typical Serebrennikov fashion, there are too many small decisions and layered details to catalogue here—clever visual metaphors, dramatic ironies, genre-blurring references. But perhaps most striking is the production’s embrace of contemporary culture. Serebrennikov injects the world of Don Giovanni with the textures of today: baby showers and hospital beds, voguing and AI-generated art, pop-cultural gestures woven seamlessly into the dramaturgy. These elements aren’t gimmicks—they’re structural. They allow for commentary on queer visibility, bi-identity, and the shifting norms of desire and power.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the casting of Don Elviro—a gender-swapped Elvira—sung with astonishing clarity and emotion by Bruno de Sá. The queerness of the characters, including Don Giovanni himself, is never turned into spectacle or shorthand; it simply is, one facet among many in the opera’s human kaleidoscope. It’s a production refreshingly free of heteronormative defaulting, which is far too rare in the operatic canon.

Opera, Oratorio, and the Space Between Worlds

As we approach Don Giovanni’s descent into the underworld, the production gradually detaches from any remaining logic. The chaos accelerates. Skeletons dance. Large phallic objects (likely just massive dildos) emerge on stage. Dancers contort in full nudity. The surrealism of his final fever dreams reaches a hallucinatory peak. And then—abstraction. The boxes vanish. The stage goes black. One lone dancer remains—possibly Don Giovanni himself, aged, stripped bare, walking through metaphysical space—while the Komische Oper choir begins the Requiem.

It’s here, in the collision between opera and oratorio, that the production finds its most powerful voice. These are not two works stitched together, but a fluid continuum. From a structural, intellectual, and musical standpoint, it’s an astonishing choice. The Requiem doesn’t just follow the opera; it is its final act. The performance ends with Lacrimosa, the last section Mozart composed before his death—and the final chapter of the Bardo Thödol, titled “Liberation”. Whether Giovanni is reborn, freed, or damned is left open. We must decide for ourselves.

Death as liberation—this, perhaps, is Serebrennikov’s most radical gesture. Carl Jung once described the funeral mass as the West’s only true “death cult,” and music like Mozart’s Requiem as composed less for the living than for the soul of the departed. In placing the Requiem here, Serebrennikov offers Don Giovanni a grace rarely afforded to him: not moral forgiveness, but spiritual compassion. A final song, not for us—but for him.

Conducting James Gaffigan

Production, Stage design and costuming Kirill Serebrennikov

Co-set designer Olga Pavlyuk

Co-costume designer Tatiana Dolmatovskaya

Co-choreography Ivan Estegneev

Choreografy Evgeny Kulagin

Dramaturgy Sophie Jira/Daniil Orlov

Choirs David Cavelius

Light design Olaf Freese/Johannes Scherfling

Video Ilya Shagalov

Don Giovanni Hubert Zapiór

Leporello Tommaso Barea

Donna Anna Adela Zaharia

Don Ottavio/Tenor Agustín Gómez

Don Elviro Bruno de Sá

Zerlina/Sopran Penny Sofroniadou

Masetto Philipp Meierhöfer

Commendatore/Bass Tijl Faveyts

The young woman/Alto Virginie Verrez

The Commendatore's soul Norbert Stöß

Donna Barbara Varvara Shmykova

The old woman Susanne Bredehöft

Don Giovanni's soul Fernando Suels Mendoza

Spirits and thought-forms Georgy Kudrenko/Mikhail Poliakov/Nikita Elenev

Chorsolisten der Komischen Oper Berlin

Orchester der Komischen Oper Berlin

Komparserie