Die schweigsame Frau at Staatsoper Berlin

Between camp and complicity, this production plays with tropes it should interrogate—and ends up reinforcing the very norms it claims to question.

🎭 Die schweigsame Frau

🎶 Richard Strauss, 1935

💭 Jan Philipp Gloger, 2025

🏛️ Staatsoper Berlin

🗓️ 24.07.2025

"EINE DUMME KLEINE, DIE DEN HERD UND HAUSHALT FÜHRT?"

Die schweigsame Frau arrives at Staatsoper Berlin with considerable historical baggage and contemporary ambition. This 2025 premiere transposes the 1935 opera—itself based on Ben Jonson's 1609 play Epicoene—into modern Berlin, yet the production reveals more about our current cultural moment than it perhaps intended.

The Weight of History

Strauss's collaboration with Jewish librettist Stefan Zweig on Die schweigsame Frau represents one of the composer's most politically fraught works. Created during his tenure as president of the Reichsmusikkammer, the opera existed in a precarious space between artistic integrity and political survival. With Strauss protecting his Jewish daughter-in-law and his grandchildren while serving as the Nazi regime's most prominent living German composer, the work's four performances in Dresden before being banned underscore the impossible position of art under totalitarianism.

The opera's comedic focus reflected a part of Strauss's post-World War I artistic philosophy—his belief that musical theater could serve as a unifying force against what he termed the "Orientierungs- und Sprachlosigkeit des Menschen der Moderne." This desire for art to provide refuge from modern complexity resonates eerily with contemporary cultural anxieties.

A Berlin Apartment as Social Mirror

This new 2025 production by Jan Philipp Gloger places the story firmly in present-day Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf: a wealthy, West Berlin Altbau becomes the central stage for a tale of generational friction, housing inequality, and, ostensibly, communal healing. The results are mixed. The staging itself is superb: visually rich, lived-in, textured with Berlin-specific detail. The production opens with a cheeky, ImmoScout-style housing portal projected onto the curtain, drawing a parallel between Strauss’s 1930s and Berlin’s current housing crisis. The set rotates elegantly, revealing new rooms as relationships shift and masks fall.

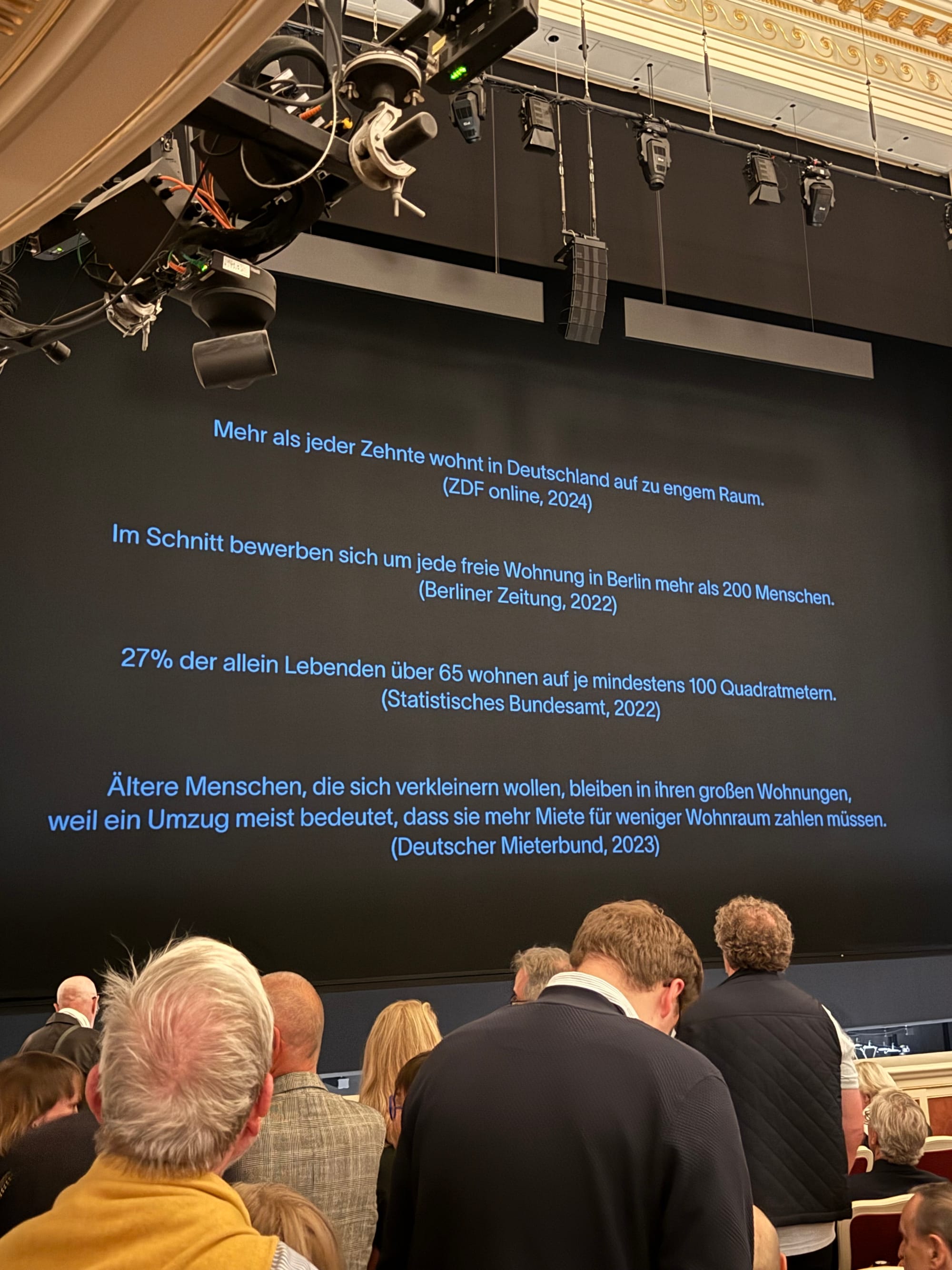

But for a work so rooted in the politics of its time, and for a production so determined to update its setting to the now, the actual sociopolitical analysis remains surprisingly shallow. Yes, we’re shown the stark contrast between a rent-controlled, oversized Altbau and a troupe of precariously housed, artist-queer-student-types. Yes, we’re told via intermission infographics that 1 in 4 seniors over 65 in Germany live alone, and that older tenants often “hoard” rent-controlled square meters they no longer need because they cannot afford to downsize. But the production never truly grapples with the structural dynamics behind these inequalities.

Queerness as Otherness

The artists are framed as “precarious,” yet are visually coded as simply urban, bohemian, queer. If anything, the message seems to lean into a tired trope: queerness = fringe. The group’s alternative lifestyle, complete with an unnecessarily sexualized, ambiguously poly dynamic and explicit physical interactions, is offered not as a legitimate counter-model to bourgeois isolation, but as a caricature of non-normative life. The program's description of these characters as "milieufremde Menschen" (people foreign to the milieu) reinforces rather than questions the bourgeois perspective that would view alternative lifestyles as inherently other. It feels dated. Lazy, even.

Perpetuating What It Claims to Critique

That same laziness shows up in how the production handles misogyny. At its heart, Die schweigsame Frau is a story built around a central misogynist joke: a man wants to marry a woman on the condition that she will be completely silent. The libretto, though witty, is saturated with gendered clichés—the nagging wife, the changed-after-marriage trope, the fury who yells too much. These lines still earn laughs from the Staatsoper audience. But the production never attempts to reframe them. Instead, it doubles down: in one particularly jarring moment, Henry—our supposed romantic lead—emerges wearing a T-shirt with the Venus symbol crossed out while simultaneously implying that he beats Aminta/Timidia into submission (albeit being part of the troupe’s intrigue). The moment raises uncomfortable questions: Is this satire? Camp? Critique? The ambiguity itself becomes the problem. When visual language carries this much charged symbolism, unclear intentions aren’t just confusing—they’re troubling, and the benefit of the doubt quickly erodes.

The deeper frustration here is that the production seems to ignore the most compelling, and most modern, aspect of the character at its center: Morosus isn’t just a grumpy old man. He’s a disabled war veteran whose hypersensitivity to sound governs his entire existence. His seclusion isn’t misanthropy—it’s trauma. And yet, this element is never named. Not in the program, not in the dramaturgy, and certainly not in the staging, which instead paints him as an emotionally cold, economically coddled bachelor who needs to be pranked into community. But this isn’t just a guy who doesn’t “get” queer theatre kids. This is someone whose physical limitations shape his social isolation. Rewriting him as simply bitter flattens the narrative—and makes the final “gotcha” twist (where everyone gangs up to trick him into joy) land less like healing and more like gaslighting.

Character as Device, Chaos as Style

Similarly, Aminta—the “silent woman” of the title—is written as a complex and sympathetic figure: reluctant to deceive, visibly uneasy with the plan, and genuinely empathetic toward Morosus. And yet, she remains reduced to a plot device—a woman caught in a scheme orchestrated by her own partner, whose emotional crisis is played for laughs and whose inner conflict is barely acknowledged. The production claims to explore themes of community, mutual care, and coexistence. But what it actually stages is a deeply individualistic manipulation, thinly disguised as togetherness. The plot and the cruelty both originate with Henry—and still, we’re asked to applaud the final reconciliation.

It’s also worth noting the production’s uneven tonal palette. Early scenes are staged with naturalistic care, while later the production veers into absurdist fantasy: judges in 17th-century robes and ghostly makeup, a Vegas-style wedding, protest posters about cancel culture (“Machos raus!”), Wednesday Addams-inspired characters, group choreographies evoking High School Musical. These aren’t inherently bad ideas. But in a production so concerned with realism—down to the Altbau’s Gründerzeit lattice windows and vintage lamps—the shift feels untethered. The chaos is “carefully planned,” as Gloger notes in the program. But what does it say about the world it intends to mirror?

Questions of Audience and Intent

That may be the biggest open question. For all its cleverness, Die schweigsame Frau ends up feeling like a production caught between irony and earnestness, between critique and complicity. The audience laughs at the old jokes, the uncle forgives, the house lights come on, the woman is silent once more.

Perhaps most significantly, this production raises concerning questions about operatic audiences and cultural backlash. The enthusiastic reception of centuries-old misogynistic humor suggests either a failure of critical distance or an audience genuinely comfortable with such perspectives. In an era of rising populism and cultural polarization, art's responsibility to challenge rather than confirm existing prejudices becomes paramount—and this production falls short of that purpose.

Reflections on Cultural Zeitgeist

Ultimately, this production may thus succeed despite itself—not as progressive theater, but as an inadvertent mirror of contemporary cultural anxieties. Its retreat into familiar tropes and its failure to meaningfully engage with the social issues it raises perhaps reflects broader cultural tendencies toward regression and simplification.

It’s tempting to say: this production just wasn’t for me. I come from a generation, and a positionality, that’s sensitive to representations of queerness, power, and trauma. I don’t want opera to flatter my worldview—but I do want it to reflect critically on the world we share. When it leans into tropes instead of interrogating them, when it squanders opportunities to examine disability, housing inequality, and gender dynamics with the nuance these issues deserve, it reinforces rather than challenges the very problems it purports to address.

Die schweigsame Frau is, on the surface, a comedy. But in a time of cultural hesitance, when public discourse grows more hostile and art institutions more risk-averse, I can’t help but wonder: what kind of laughter are we reinforcing—and who is really in on the joke?

:blur(20):quality(10)/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.staatsoper-berlin.de%2Fdownloads-b%2Fde%2Fmedia%2F66114%2Faf97b30160b206585dd70bdb69760e14%2FSchweigsame%20Frau_123.jpg)

Cast

Musical Director: Christian Thielemann

Director: Jan Philipp Gloger

Set Design: Ben Baur

Costumes: Justina Klimczyk

Light: Tobias Krauß

Video: Leonard Wölfl

Choreography: Florian Hurler

Chorus Master: Dani Juris

Sir Morosus: Peter Rose

His housekeeper: Iris Vermillion

Barbier Schneidebart: Samuel Hasselhorn

Henry Morosus: Siyabonga Maqungo

Aminta, his wife: Brenda Rae

Isotta: Serafina Starke

Carlotta: Rebecka Wallroth

Morbio: Dionysios Avgerinos

Vanuzzi: Manuel Winckhler

Farfallo: Friedrich Hamel

Staatsopernchor

Staatskapelle Berlin