Boris Godunov at Dutch National Opera

A searing, harrowing, emotionally devastating production that turns Mussorgsky’s opera into a portrait of complicity, grief, and the cost of silence.

🎭 Boris Godunov | General Rehearsal

🎶 Modest Mussorgsky, 1872

💭 Kirill Serebrennikov, 2025

🏛️ Dutch National Opera

🗓️ 08.06.2025

“POWER IS COMPLETELY DEPENDENT ON OUR OBEDIENCE. ON OUR CONSENT.”

Where to even begin? I’m rarely so deeply moved by anything on stage. I attended this performance of Boris Godunov with a Russian friend “in exile,” and witnessing her reactions in real time—flinches of recognition, quiet tears, occasional stifled sobs—was as affecting as the opera itself, if not more. This wasn’t just an evening at the theatre; it was an act of witness. A glimpse into what it means to love a country that no longer feels like home.

In this 2025 production at the Dutch National Opera, Kirill Serebrennikov stages the 1872 version of Mussorgsky’s Boris, with the original 1869 coronation scene inserted. The result is a breathtaking, brutal allegory of contemporary Russia—its ghosts, its absurdities, and the lives of those navigating them.

History as Obligation

The opera itself draws from a brief, turbulent moment in Russian history: Boris Godunov ruled around the turn of the 17th century after the death of Ivan the Terrible and before the rise of the Romanovs. Mussorgsky composed it in the mid-19th century, at a time when reflecting on Russian history was considered not just artistically fashionable, but intellectually obligatory. This was a period shaped by historians like Nikolay Karamzin, who constructed a national narrative that made past and present feel urgently connected. Serebrennikov follows in that lineage—but with the tools and language of our time. His Boris is not just a historical drama, it is a brutal, bleak allegory of contemporary Russia, told with unflinching intimacy.

A Portrait of Russia Today

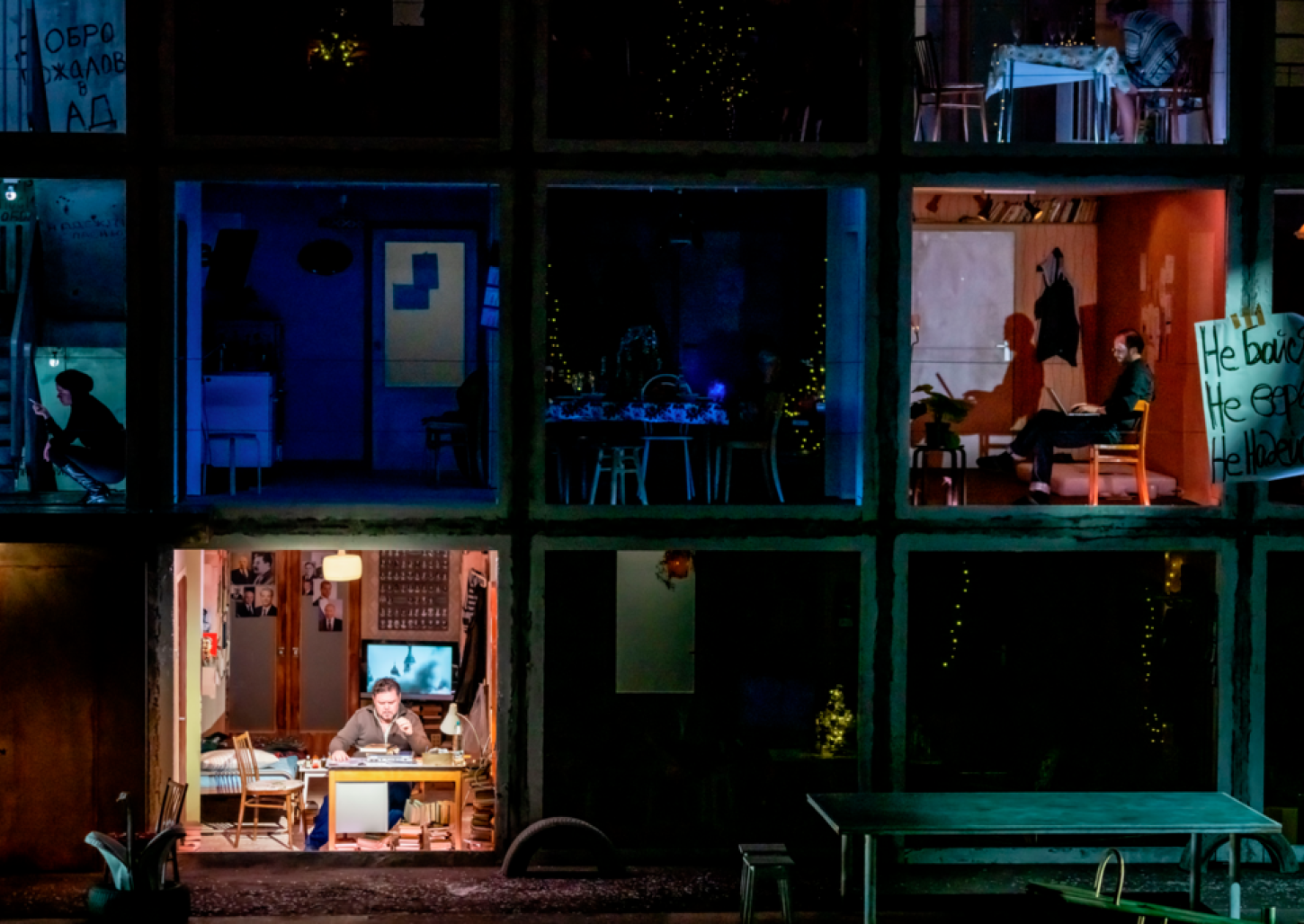

The Holy Fool, traditionally a prophetic outsider, becomes a modern political dissident—a “Simple Man” just released from ten days of solitary confinement. His monologues, scattered throughout the opera, are drawn verbatim from the courtroom testimonies of real Russian activists. Elsewhere, Mussorgsky’s characters are transposed into a grim cross-section of modern Russian life. Grigory, the young pretender to the throne, is now a bicycle courier, introduced as he wheels his delivery bike across the stage. A coronation becomes a televised New Year's speech. We see nurses, sex workers, policemen, bureaucrats, widows, TV anchors. Even the most minor roles feel specific and real. The Orthodox morning prayer, typically an abstract choral moment, here becomes the soundtrack to a team of street sweepers cleaning the pavement outside the prefab apartment block that serves as the production’s main set.

This three-story block—somewhere in provincial Russia, just one of thousands like it—is where nearly all the action unfolds. The delivery backpack worn by Grigory reads “Uglich Delivery,” our only clue to the location. Uglich, of course, is the Russian town in which Tsarevich Dmitriy Ivanovich died in 1591 under mysterious circumstances at the age of eight—a crime later blamed on the real Boris Godunov.

Behind each window of the apartment block, a fragment of daily life: a mother mourning a son killed in combat; a young man attempting, and failing, to perform with a sex worker; neighbors exchanging tense glances in the stairwell; families receiving bureaucratic consolation prizes in exchange for their dead. War is omnipresent: propaganda flickers across the TV sets, "Z" symbols are displayed time and again, portraits of fallen soldiers stare out from tiny living rooms, widows don signatory ribbons. In one haunting sequence, a press ceremony unfolds in which grieving women are awarded plaques for the death of their loved ones. My friend confirmed later: this happens, exactly like this, every day in Russia. Only that in real life, consolation prizes include kitchen appliances and household items.

Made for Russians, At Home and Abroad

The brilliance of Serebrennikov’s production lies in this specificity. Every detail is chosen not to generalize but to reflect. It is a production made for Russians—both those who remain, and those who have left. Like the late Dima Markov, the photographer whose images are unfurled throughout the opera, Serebrennikov aims to show unvarnished Russia “with love, compassion, and a tender inner light.” That tenderness comes through, even in the bleakest moments.

The set feels lived-in. The costumes are authentic. Behind-the-scenes pictures confirm that even on walls and surfaces impossible to be noticed by the audience, tiny details speak of Russian daily life. There’s no satire here, no irony—just exhaustion. And when I looked around the audience during the general rehearsal, many of whom were Russian, I saw people weeping, gasping, nodding slowly in grim recognition. For them, this wasn’t a metaphor. It was home.

The Conspiracy and the Couch

But Serebrennikov is not only interested in intimacy. He’s also interested in critique. And nowhere is that clearer than in the infamous “Polish act” of the opera—Act III—long considered an awkward appendage to the rest of the drama (Mussorgsky added it only after critics complained the original version lacked women's voices). It centers Marina Mniszek, a Polish noblewoman who believes she has a rightful claim to the Russian throne.

But instead of staging this as straightforward political intrigue, Serebrennikov turns it into a parody of a glossy American political thriller—something from Shondaland, perhaps, replete with sleek lighting, dramatic close-ups, and a powerful Black woman in an Olivia-Pope-Hillary-Clinton suit ensemble who plays the U.S. President. The show within the show is called The Conspiracy, and it’s presented as a kind of propaganda-laced fever dream. President Marina sings about destroying the “Russian nest”—language that echoes Western narratives of regime change and anti-Russian sentiment.

We see this entire act through the eyes of Grigory, the delivery driver, who watches the show on his battered TV. Eventually, he enters the show itself—literally becoming a character in his own fantasy. The message is clear: media has replaced reality. Even dissent, even rebellion, gets filtered through the language of entertainment. At one point, Marina says to Grigory, “You dream of me day and night, you forget about your fight against Tsar Boris.” In other words, distraction is complicity. The people are too busy consuming to resist. Too fixated on narrative to recognize truth.

This theme—the impossibility of opposition—is central to the production. Serebrennikov shows us two kinds of resistance: the activist, who goes to prison for holding a banner; and the chronicler, a royalist historian who hates Boris not for his authoritarianism, but for murdering the rightful heir. One is a revolutionary, the other a nostalgic monarchist. They share an enemy but not a cause. This fragmentation, this failure to align, mirrors the reality of fractured opposition movements today. Even when people want change, they don’t always want the same kind of change. And so nothing changes.

The Tragedy of Humanizing Power

Meanwhile, Boris himself looms large. In the opera’s original libretto, he is humanized—a leader haunted by guilt, grappling with visions of the murdered child he may or may not have killed to seize the throne. But in this production, any such humanization becomes almost uncomfortable. Because this Boris is clearly, unmistakably Putin. The mannerisms, the gestures, the speeches—it’s all there. At times, the resemblance to Stalin is also emphasized, creating an amalgam of Russian strongmen. The result is a strange kind of dissonance. The opera tries to show Boris as a flawed man. But the production makes clear: this man, today, is a monster.

As the opera approaches its end, Serebrennikov leans into his signature absurdity. The lighting shifts. Chorus members don Orthodox halos, cardboard cut-out swords and shields. An additional stylized, theatrical, surreal layer is added on top of the unfolding plot onstage. And finally, as Boris succumbs to his mental and physical torment, violence erupts in every apartment. People turn on one another. The state is collapsing, but no one is rising up—people are too preoccupied with petty infighting. It’s a vision of disintegration, not revolution. And all the while, the chorus sings of glory, of blood, of Russia’s eternal destiny. It’s harrowing.

There’s no resolution, no catharsis. Boris dies. Prince Shuisky, a potential political rival, hints at a coming power vacuum. Historically, this was a real period of crisis—the “Time of Troubles”—which ended with the rise of the Romanovs and three centuries more of imperial rule. The implication is clear: we’ve been here before, and we’ll be here again. The wheel keeps turning: oppression, collapse, revolution, repression. From tsars to Soviets to oligarchs, nothing breaks the cycle. At the end, all that remains is noise, violence—and silence.

What Lingers

In the days after, I couldn’t stop thinking about the performance. Neither could my friend. We kept talking about the smallest details—how the wallpaper in one apartment looked exactly like the one in her childhood home; how Russian state TV actually shows microwaves being handed out to grieving families. What lingered most was the feeling of recognition—and of pain. “It’s like a punch in the gut,” she said. “To see your country shown like this. And to know it’s true.”

What Boris Godunov gave me was not just a deeper understanding of Russia today, but a deeper sense of empathy for the people trying to survive it. The ones who remain. The ones who leave. The ones who speak out. The ones who stay silent because they’re afraid. I came away humbled, shaken, and grateful. This wasn’t just a powerful production. It was an act of resistance—and an act of love.

Musical direction Vasily Petrenko

Stage director, set and costume designer Kirill Serebrennikov

Co-director and choreographer Evgeny Kulagin

Co-set designer Olga Pavliuk

Co-costume designer Tatiana Dolmatovskaya

Lighting designer Sergey Kucher

Video designer Yurii Karikh

Dramaturgy Daniil Orlov

Boris Godunov Tomasz Konieczny

Feodor David van Laar

Xenia Inna Demenkova

Nurse Polly Leech

Prince Vassily Ivanovich Shuisky Ya-Chung Huang

Andrei Shchelkalov Jasurbek Khaydarov

Pimen Vitalij Kowaljow

Grigori Dumitru Mîțu

Marina Mnishek Raehann Bryce-Davis

Rangoni Gevorg Hakobyan

Varlaam / Mitiukha ShenYang

Missail / Boyar Steven van der Linden*

The Hostess of the Inn Eva Kroon

Yurodivy ('A Simple Man') Odin Lund Biron

Nikitich Roger Smeets

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Chorus master Edward Ananian-Cooper

Nieuw Amsterdams Children’s Chorus (part of Nieuw Vocaal Amsterdam)

Chorus master Pia Pleijsier

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra