Andrea Chenier at Deutsche Oper Berlin

Power tilts, collapses, and reshapes in this searing production—a physical meditation on revolution, wealth, and who gets to fall.

🎭 Andrea Chenier

🎶 Umberto Giordano, 1896

💭 John Dew, 1994

🏛️ Deutsche Oper Berlin

🗓️ 04.06.2025

"THE REVOLUTION DEVOURS ITS CHILDREN"

What makes this 1990s Andrea Chénier revival at Deutsche Oper Berlin so unsettlingly relevant isn’t its fidelity to historical detail—it’s the way it stages revolution not as a backdrop, but as a physical force. Here, political upheaval doesn’t just ripple through arias and declarations. It shifts the literal ground beneath the characters’ feet.

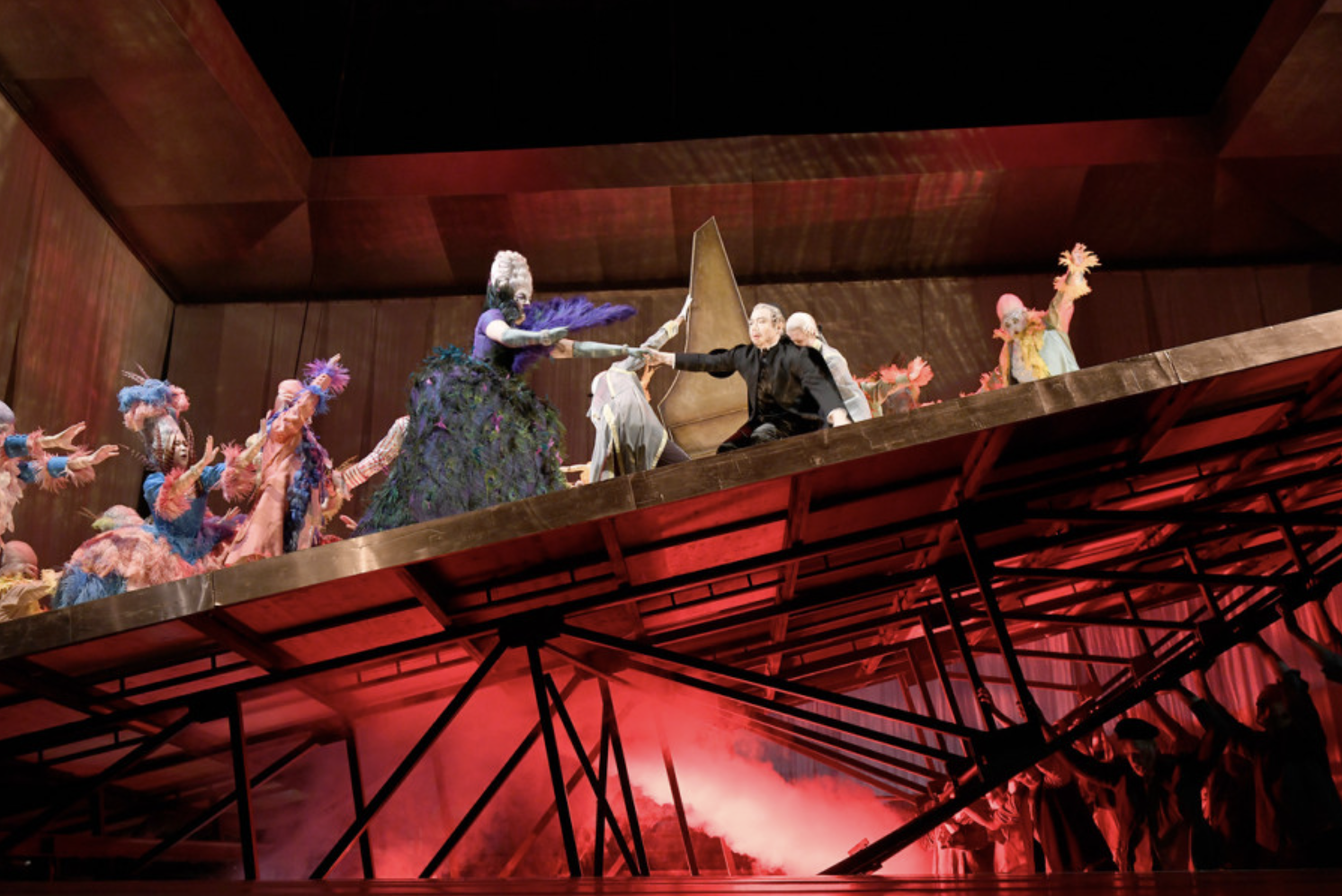

A massive cantilever is placed onstage, tilting ominously with each act. In Act I, we are high above the fray, watching the French aristocracy host an opulent party in a provincial château. The costumes are wildly baroque: feathered, glittering, borderline absurd. They don’t aim for historical realism. Instead, they signal a different kind of truth—a grotesque exaggeration of class excess, almost parodic in its wealth display. Think Hunger Games reimagined by a 1990s costume house. It’s funny, until it isn’t.

Because the party is interrupted—from below. Literally. The poor rise from under the stage, crawling out of darkness and into the ballroom. It’s a brilliant, violent metaphor: social revolution as vertical intrusion. The aristocrats, oblivious until the last moment, are physically displaced. The golden furniture slides, dancers stumble, and the stage tilts. Revolution is not a story here; it’s an architectural collapse.

But what replaces the old order? Act II answers with a kind of ambivalence. The slogans of Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité are scrawled across the set in bold type, then drenched in red light—subtly mocking the idealism they once represented. Gérard, the servant-turned-revolutionary-politician, mirrors Tosca’s Scarpia: he uses power to pursue Maddalena, just as Scarpia manipulates Tosca. But where Scarpia is unrepentant, Gérard begins to change—cracked open by Maddalena’s equally devastating and iconic aria “La mamma morta.” It’s a spiritual sibling to “Vissi d’arte,” a moment where private grief breaks into public horror, and where soliloquy paves the way for character transformation. Unlike Scarpia, Gérard recoils from what he’s become. But the damage is already done.

This production is not interested in neat moral arcs. It wants to show systems, not heroes. The final act returns to that giant tilting stage—now tilting (collapsing?) in the opposite direction, symbolizing not justice restored but power rebalanced again, and again, and again. The revolution devours its children. Chénier, the poetic idealist, dies not because he betrayed the cause but because he no longer fits into it. By the end, black curtains close in on both sides, and from above, the shadow of a guillotine falls. No blood is shown; it doesn’t have to be. The image is absolute.

What lingers isn’t just the tragedy of Chénier and Maddalena, but the bleak insight that history doesn’t move forward—it lurches. Topples. Crushes those beneath. And maybe that’s why this 1990s production feels more urgent than ever. Because while the aesthetics of power have changed, its mechanics have not. The French aristocrats in Act I were at least ostentatious and unapologetic in their decay—patrons of artisanship, architecture, even beauty, at least when viewed through a contemporary lens, and with lots of hindsight.

Today’s billionaires are more elusive. They shun taste, and the public sphere entirely. Their wealth doesn’t spill over into art or costume or space; it vanishes into servers, stock buybacks, and private islands. We no longer see them waltz—we read about them buying entire cities or staging weddings that shut down Venice. But unlike the doomed aristocrats of Andrea Chénier, they rarely have to answer to mobs, or mobs don’t even reach their doors.

This production reminds us that power is never fixed or absolute. But it also asks a harder question: who gets to fall theatrically, and who disappears offstage entirely?

Cast - 04.06.2025

Conductor Axel Kober

Director John Dew

Stage design Peter Sykora

Costume design José Manuel Vázquez

Chorus Master Jeremy Bines

Andrea Chenier Gregory Kunde

Carlo Gérard Pavel Yankovsky

Maddalena di Coigny Sondra Radvanovsky

Bersi Arianna Manganello

Contessa di Coigny Nicole Piccolomini

Madelon Jennifer Larmore

Roucher Padraic Rowan

Pierre Fléville Philipp Jekal

Abbé Kangyoon Shine Lee

Matthieu Michael Bachtadze

Incroyable Burkhard Ulrich

Majordomo / Dumas Stephen Marsh

Fouquier-Tinville Jared Werlein

Schmidt Byung Gil Kim

Chorus Chor der Deutschen Oper Berlin

Orchestra Orchester der Deutschen Oper Berlin